Thirty years ago on 20th August, Blur beat Oasis in the Battle of Britpop. I bought ‘Country House’ of course. I was 16 in 1995, obsessed with reading the NME and Melody Maker, and dreaming of going to gigs. I wore Manics eyeliner and nicked my sister’s fake fur coat. Half the world away, James Cook was practising his bass guitar and riding buses to London’s Camden to buy the NME with his band Flamingoes actually in its review pages. The glam-power-pop trio fronted by good-looking twins (Jude Cook on vocals) was, in theory, mid-’90s catnip, with glorious nail varnishy dashes of Roxy Music and Bowie. In other words, right up my street.

So why did I never find them? I chat to James – author of the beautiful Memory Songs – in quest of the answer.

AD: First up, how did Flamingoes come to be? And was it just chance that the band collided with peak Britpop?

JC: Flamingoes was dreamt up after drummer Simon Gilbert left the band my brother Jude and I had formed, The Shade, in 1991, for a completely unknown London group – Suede. It took them a year of struggle to get to that famous Melody Maker front page – “The Best New Band In Britain” – and after that Simon was on a newspaper or magazine cover pretty much every week. That’s quite an incentive, added to the fact we’d been writing songs for 10 years and starving on the dole for four of those in London. We were on our last legs, exhausted, and we were only 23!

We were serious young men, perhaps too serious. Our influences were similar to Suede and a dozen other bands we didn’t know about who were all working away trying to establish themselves. A great ferment was under way, creatively, in London. “Everyone’s dreaming of all they’ve got to live for,” as Saint Etienne sang in 1993. The term Britpop was still in the future.

‘Echobelly pissed all over Oasis as a live band’

AD: In your book Memory Songs, you describe a moment in 1993 when you say you realised that “something was happening here” (your new drummer Kevin turning up in eyeliner and Blur ditching baggy for The Kinks with Modern Life is Rubbish). Which Britpop bands did you feel kinship with? And which not… ?

I felt a certain kinship with Suede, the Manics (not really Britpop, but contemporaneous I suppose), Shampoo, Pulp, Elastica to a degree, and Echobelly. But none with Oasis, Cast, Ocean Colour Scene, Bluetones, etc, even Blur, which was probably just me personally; I couldn’t understand how anyone could love Damon’s faux-yob voice, although I admired his songwriting and the rest of the musicians in the group, and played Parklife to death . . . The other bands were just lads – it got very laddish very quickly – and Flamingoes weren’t lads, we were trembling aesthetes (or at least I thought I was!)

AD: There’s a moment where you are very much “on the cusp” of a major breakthrough. Tell me about how it felt…

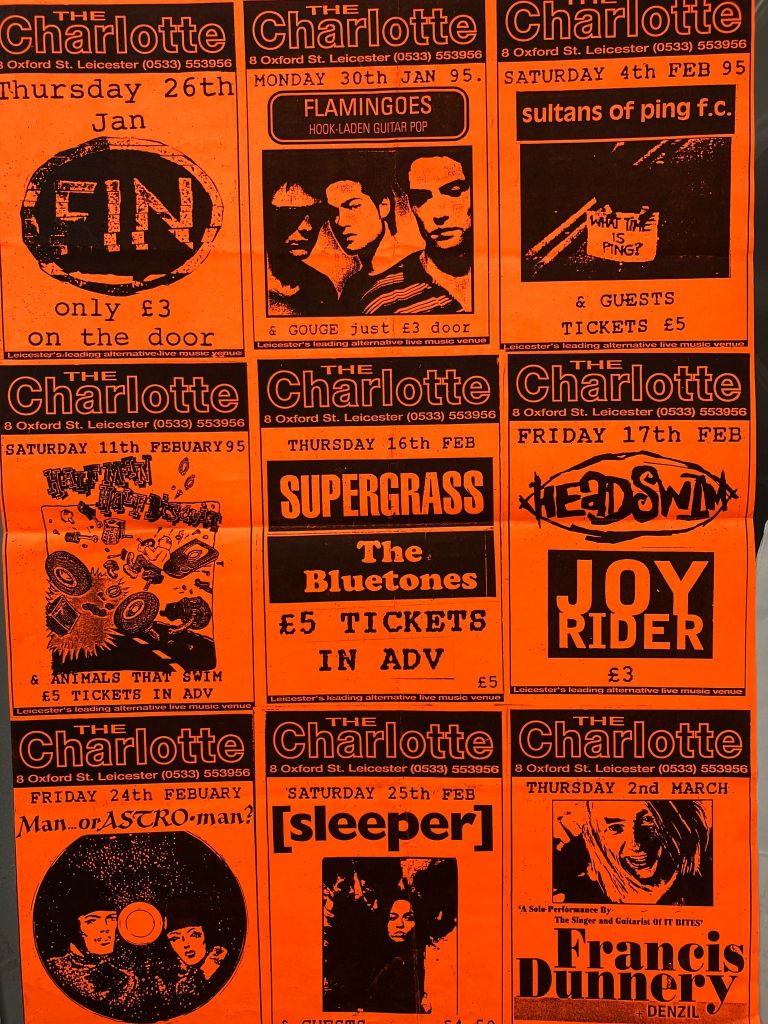

JC: I found a flyer from Sheffield Leadmill (‘Voted third best live venue in UK!’), October ’94, and in one month they put on These Animal Men, Elastica, Ash, Shed 7, Supergrass, Green Day, and Flamingoes. Apart from Green Day, obviously, all these new bands were on the starting blocks, waiting to take off. It was unbelievably exciting. After a 10-year apprenticeship, it finally felt as if we were “going in”; that it was almost pre-ordained. We had daytime Radio One airplay and were “hotly tipped for the top” in both Melody Maker and NME. Of course, we didn’t know that the gatekeepers of the press would finally decide who was chosen or not. We were about to find out…

AD: Which bands did you get support slots with from the established scene, and who was supportive generally?

JC: The only bands we really supported were Mantaray and Echobelly (UK and European tours). Cast supported us once at The Monarch in Camden. Echobelly were incredibly supportive and generous. The first time we met Sonya [Madan], in summer 1994, the first date of the tour, Jude and I were so nervous we both went in to shake her hand at the same time. She was on the cover of the Melody Maker that week (‘All Hail Queen Sonya!’). She was sweet about it, very cool. An amazing frontperson and singer. In fact, the group were amazing, they pissed all over Oasis as a live band. There were some other bands we played with that I really liked: Tiny Monroe, Drugstore, a few others. All female-fronted, I realise now. There’s a misconception that Britpop was just blokes, not helped by the fact that the big three – Oasis, Blur, Pulp – were all male, but women were making some of the most interesting records, and were influenced not just by the usual Beatles, Kinks, blah but by Huggy Bear, PJ Harvey, and [the] Riot Grrl [scene].

AD: What about rivalries – we all know about Blur v Oasis – did you have any arch enemies?

JC: In Memory Songs I write: ‘the prevailing tenor of the time was one of rivalry, a dirty civil war among the groups’, and I haven’t reversed that opinion since. The bands quickly realised there was only limited space in the inkies and Radio One playlists, so we were all pitched into daggers-drawn conflict with each other. And remember we were all in our early 20s and hugely ambitious. Some (like us) had screwed up their education to follow a music career so the stakes were sky high. Also, the ‘90s was a very bitchy era generally, everyone seemed to be in full-on irony/sarcasm mode all the time. It wore me out, as Thom Yorke sang. So, to answer your question, our arch enemies were EVERYONE!

‘Whatever the reasons, at some editorial meeting it was decided there was no room for Flamingoes’

AD: How did you view the power of the music press at the time?

JC: The journalists were vicious and partisan, one eye on future media careers… It’s difficult to grasp the power the press had at the time, living as we do [now] in a fragmented digital age. The three main titles, Sounds, Melody Maker, and NME were comprised of a committee of unelected tastemakers who could literally decide if a band had a future or not. The only comparison was probably Broadway theatre critics. Most of these guys (and they were mostly guys) were the same age or not much older than the bands, and like us they were arrogant and had big egos. Also, journalists were viewed as parasites by the bigger artists, so maybe they took it out on groups lower down the food chain. Whatever the reasons, at some editorial meeting it was decided there was no room for Flamingoes, despite the fact we had some loyal supporters at the papers.

AD: Did you ever want to be categorised as “Britpop”?

JC: Never. I thought it was a lazy catch-all expression designed to sell papers, just as Girl Power would be later in the decade. It became the scene no-one wanted to belong to, even though the exposure, if you hitched yourself to the bandwagon, was massive. Good bands know that there’s built-in obsolescence to a scene and run in the other direction. And by the time the term Britpop was everywhere, in summer 1995, we were done.

AD: In your view, why didn’t 16-year-old me find you…?

JC: I think there was only so much room in the press. We did have a superb press company working for us, though, Hall or Nothing, and our rep, Caffy was the best in the business. She pretty much single-handedly made sure Radiohead had a career, when the press despised them because they were signed to The Man (EMI). This was around the time of Pablo Honey. They could easily have been dropped and got “proper” jobs. No The Bends, no OK Computer. But Caffy wouldn’t give up. It took Caffy a year of banging on doors to get us our tiny Melody Maker and NME features. So if you missed those issues you probably wouldn’t have been aware of us.

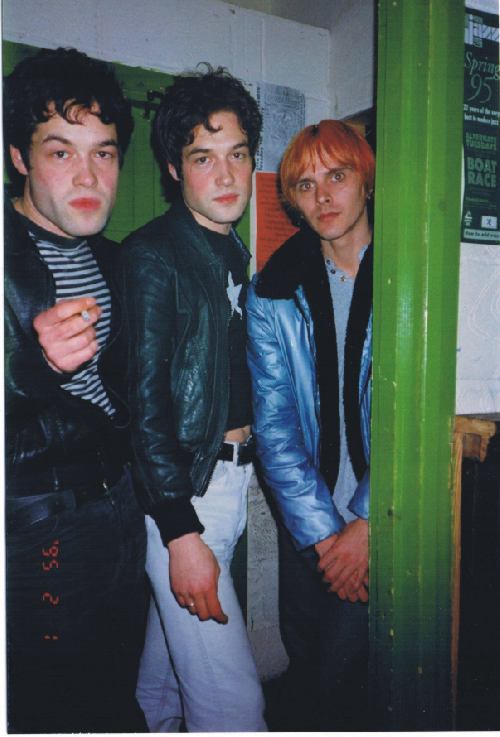

Here I am not finding Flamingoes despite having the same hair. I was gutted when “Britpop” and “Oasis” became almost interchangeable terms. I wanted Neil Hannon (The Divine Comedy) in his cravate and I wanted Jake from My Life Story with his teardrops and I quite liked seeing Nicky Wire in a dress. I definitely wanted to be Justine Frischmann in a cool black Fred Perry. The fact that Oasis seemed to legitimise the school bullies again – a boy in nail varnish risked a beating in my home town – was depressing. I spent my first year in Leeds (1998) armed with an eyeliner in my pocket so that I could “convert” Mods into glammer boys at whim. Anna Doble

AD: Any regrets about that era?

JC: Hundreds! No, not really. Jude and I tried our damnedest, we had the usual bad luck that bands have. We looked like two Renaissance princes back then, pin-ups (hard to believe now!), and we could write songs. We had to give it our all.

I don’t envy those bands having to tour their one big album on the circuit now in their 50s. I was constitutionally unsuited to touring anyway. If we’d have been a big band, gone to America, I’d be dead now, no doubt about it.

AD: Can you see a Britpop-style phenomenon ever happening again – a music scene that infiltrated the nation’s living rooms – or do we consign it to a pre-internet age?

JC: Sadly, no. The pop-cultural fragmentation that occurred post-internet – and the fact that music could be accessed for free – put an end to such all-pervasive scenes. But saying ‘Our party was the Last Party’ denies a 16-year-old today their own special era. Yes, Britpop was significant, important, but important to whom? If there’s one group or artist, however obscure, that they care passionately about, that belongs to them, that’s all that matters. I know there are one or two people still out there who see Flamingoes as that group, which makes all the struggle and sacrifice worthwhile.

Read the full version of this interview where James turns the tables on me (!!) for Drowned in Sound – Inside the other Britpop

James Cook is author of Memory Songs: A Personal Journey into the Music that Shaped the ‘90s (Unbound)

Read more: Connection is a Song – A book about you