Liam Gallagher is in his round John Lennon sunglasses, sat in a chair, up in the air, stuck to a wall. He’s singing ‘Live Forever’, a song at the melodic and sunny intersection between the decade’s new optimism and the peacocking laddish swagger to come. In a sense, it is the ’90s in one song. A time of forward momentum, a promise of immortality, but still dressed in yesterday’s clothes. It might be the sweetest Oasis song… it isn’t overplayed like ‘Wonderwall’, and it doesn’t have coke in its nostrils like ‘Champagne Supernova’.

In shops, magazines and in my peripheral vision, the cover art of ‘Live Forever’ keeps drawing me in. I’m stubbornly a Blur fan, but I’m intrigued by the sense of distant nostalgia: a 1930s semi-detached house in the suburbs of an English town or city, framed by fluffy black and white trees, rustling in the breeze of a July day. It is somebody else’s sighing summer. Between two brick posts, there’s a wrought-iron gate inviting us onto the driveway. It feels safe and familiar, a street we’ve kicked a deflated football down. But there’s also an unreachable, dream-like quality. It is a childhood we remember but can no longer touch. The house in the picture is John Lennon’s boyhood home at 251 Menlove Avenue in Liverpool. Coupled with the track’s title, it evokes instant melancholia. Once again, I am feeling nostalgic for things I’ve yet to know.

May-beeeeh…. It’s every moment of a night out in provincial ’90s England rolled into two drawn-out vowels

‘We see things they’ll never see,’ started out as a wistful line, maybe about the idea of living into an endless future but, to me, it is a lyric that describes the joy of noticing things that seem to pass others by. I sit on trains, with my Walkman on, seeing the sun behind a row of factory buildings outside Doncaster, and – my face reflected in the thick glass – I watch my own film. Oasis’s lyric is also a brag used by football fans to wind up rival supporters who’ve likely seen less silverware in the trophy cabinets at their clubs. You see the words on stickers peppering the London Underground after match days.

They are the words that set up the chorus of ‘Live Forever’, the jumping-off point. From his chair up in the sky, Liam is questioning himself – ‘maybe I just don’t believe’ – before bringing us, the listener, into his world – ‘maybe you’re the same as me’ – and asking us to feel what he is feeling, which is an agitated sense of hope. We see things others can’t see: it’s the high expectation of the mid-’90s and, in its poetic arrogance, the phrase contains the true essence of the brothers.

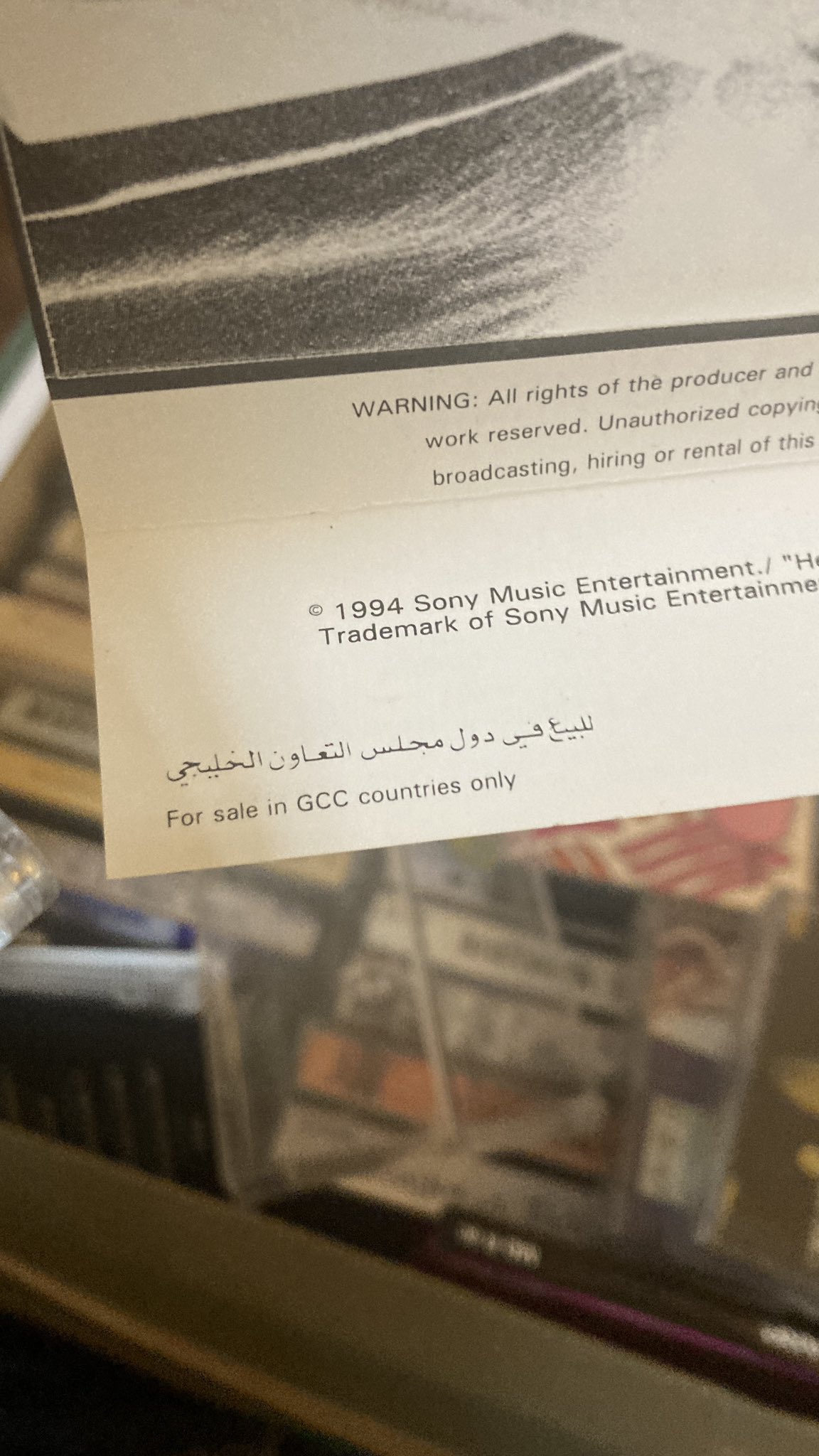

‘Live Forever’ is the third single from Definitely Maybe, the most talked-about debut album of the decade so far. I buy the album furtively on Knaresborough market a few months after its release and for a while I am confused by the cassette inlay because ‘Cigarettes and Alcohol’, the single that follows ‘Live Forever’, is listed simply as ‘Cigarettes’. And then I notice a sticker on the box which declares it ‘for sale in GCC [Gulf Cooperation Council] countries only’. How this copy found its way to the three-quid stall, next to the man my mum buys rhubarb from, we’ll never know.

I’m steadfastly a Blur fan, with scars to show it from 1995’s Battle of Britpop, but I can’t help myself loving the way Liam Gallagher sings ‘may-beeeeh’ in the opening line of ‘Live Forever’. It’s every moment of a night out in provincial ’90s England rolled into two drawn-out vowels. It’s the world I know, just like Lennon’s faded suburbia. I stand forever in the morning rain that ‘soaks you to the booone’ on a piss-wet pavement glistening at the bus stop, fag ends bleeding their brown goo into the cracks as I look down at my dirty Dunlop Green Flash feet.

Back in 1996, Noel and Liam Gallagher are riding past me on a golf buggy through thousands of Oasis fans who don’t notice it’s them until they are gone. The brothers are cruising at speed across Knebworth Park’s knobbly grass, which is strewn with plastic cups. Liam is pointing to random people, he shouts something, and now he’s throwing his head back in laughter. We see things they’ll never see: a glimpse of their own sweaty Adidas disciples.

We have fought to be here through the chugging fumes of hundreds of coaches, lined up side-by-side on dry earth in a universe of stumbling day-trippers. White plastic cords looped between metal poles hem us in, creating a temporary order, as kids in bucket hats trip through queues in search of their own Spike Island. The park’s outer edges are soundtracked by Supernova Radio, an Oasis only zone. I feel both excited and sick, glancing down to check that my shirt’s Blur logo is visible. As the lights dip, anticipation rises like cider-flavoured ocean spray from the sea of swaying fans. Liam Gallagher is dressed all in white, like a priest, and fi rst sings his own version of Blur’s ‘Parklife’. ‘All the people, so many people, and we allll go hand in hand,’ he slurs, like a drunk man trying to find the coin slot in the jukebox. I look across at my friend Andy and we grin. The crowd surges, the tinder earth scratching the soles of 100,000 pairs of trainers. Liam performs his own songs much too fast as he looks out across his never-ending fandom, and so we all sing along at a breathless pace too.

‘Wonderwall’ is over and out in two minutes. Lads in Manchester City shirts flail on shoulders. Girls with sunburn reach to catch a flying drumstick. ‘Live Forever’, there it is, the anthem of now, maybe of tomorrow, and we sing it like we mean it, as beer sploshes expensively into the dusty dirt. Later we stagger, lost but laughing, inhaling more coach fumes, as we seek the road home back to Yorkshire. I bundle the concert programme to safety, still flat and glossy beneath my Blur shirt with its imaginary perfect castle.

This is an edited extract from Connection is a Song: Coming Up and Coming Out Through the Music of the ’90s which is available now in paperback.

Anna Doble, July 2025