It’s Christmas so here is the gift of chapter sixteen from my book, Connection is a Song: Coming Up and Coming Out Through the Music of the ’90s. In this part of the story I am old enough to be given the responsibility of carrying the crucifix (a huge brass cross on top of a wooden pole) at midnight mass on Christmas Eve. But I am also a very silly teenager who has drunk far too much Sheridan’s… yes, that sickly, creamy liqueur that comes in two colours. Can I survive my own stupidity? With help from Belle & Sebastian and Gay Dad….

He has the same initials as the Messiah, I realise, and tell Claire. It is Mum who has signed us up to being church servers and, as much as we roll our eyes, we don’t want to let her down. After Claire’s Pulp epiphany, I try my best to spend my church time in a pop-video state of mind. I already know that there is a religious feeling to pop fandom so, in my head, I toy with Madonna’s rosary beads. It is my own ‘Like a Prayer’, imagining the cool brown wood around my wrists, a black Jesus dripping waxy tears onto the stone floor at my feet. And then I see the stooping figure of Belle and Sebastian’s Stuart Murdoch kneeling to pray after sweeping up shiny little pools of disco dust that have fallen through the stained glass windows in the Sunday sun.

On this Christmas night, I am leading the choir into midnight mass, which everyone knows is the most exciting service of the year. St John’s is a near 1,000-year-old church that teeters on top of Knaresborough’s famous Crag close to Waterbag Bank, a steep cobbled street that leads tourists and drunk teenagers down to the river. I think of the generations of worshippers who have walked across the smooth fl agstones up to these large wooden doors before me – and none of them spangled by afternoon drinking. This is the most important crucifer job. It is a great honour. I have been chosen because they think I’m sensible.

I am absolutely wasted.

*

Belle and Sebastian are a mysterious Scottish band whose singer is a church caretaker who lives in a fl at above a church hall. The band arrive on the pop scene like a freshly inked fanzine in 1996 and Claire gets their debut album Tigermilk on tape. We listen together with intrigued devotion and agree that the music makes us feel that it must have existed before, perhaps hidden in a library, recorded in a room that smells of the fake burgundy velvet inside a violin case. We swim in its Polaroid nostalgia, hungry to create our own version of these longed-for yesterdays that might yet happen tomorrow. The songs make us lament the rain that fell on a sports day twenty years ago, our plimsoles threadbare at the toes, our thin pale arms dappled in beads of water. The new-old sound of Tigermilk also thrusts us into the Glasgow indie scene that we suspect is happening – without us – right now on Sauchiehall Street in the pale light of a spring afternoon.

The first song on the album is ‘The State I Am In’, which introduces us to Murdoch’s fragile vocal, weaving its way across a sparse acoustic guitar. The song blossoms with chiming, sunny chords and a reference to a happy day in 1975, which seems immediately both funny and sorrowful (just one day of happiness for seven-year old Stuart). A softly brushed drum then laces a melody that seems always to have been in our heads, echoing from the room above the church. The track is playful despite the melancholia; it is Nick Drake without the overwhelming sadness. As Claire and I listen, we eagerly learn the stories of numerous intriguing characters who make up the world of Belle and Sebastian, threaded together by terry towelling shorts, trips to Marks & Spencer and flute solos.

There is a child bride, a gay brother (who has ‘confessed’) and a crippled friend whose crutches Murdoch kicks, shocking me afresh on each listen (he cures her, allegedly). There is a priest with a photographic memory who takes away Murdoch’s sins and writes ‘a pocket novel called The State That I Am In’. There’s a school where ‘the boys go with boys and the girls with girls’ and someone in Glasgow will know it is them when Murdoch declares ‘riding on city buses for a hobby is sad’. I later find myself taking the circular routes in Leeds with New Order on my minidisc player – and they are the saddest little happy hours in my week.

Back in Claire’s bedroom, Murdoch is puzzled by a dream that stays with him all day in 1995. Listening, trying to unpick the meaning, we revel in this mysterious nostalgia that is not ours and we delight in being wistful about a year that has only just passed.

With its Smithsy artwork (monochrome visions of life inside a kitchen-sink drama; paperback covers that seem to offer their own Choose Your Own Adventure backstory), it could not be more up our alley and – as usual – I follow Claire into a new pop meadow that is sprouting with both wildflowers and an unexpected view across the city.

Cliff Jones has nice hair and I feel ready to fall in love with a new pop star: all the better if he makes church more interesting

My head feels weirdly loose on my neck. Nobody knows that I’ve been drinking sweet, sickly liqueurs since lunchtime, clinking my glass with reckless abandon across the glass coff ee table at Yorkie’s house. I’ve added a pint of lager to the cocktail of stupidity. I have tried to sober up with water, a packet of crisps (Seabrooks, ready salted) and gasps of December air, but time taunts me as the hands on the clock tick dreadfully to midnight without a care for the absolute state that I am in. As usual, we assemble in the vestry and I pull on my white nylon cassock, hoping it will somehow begin to cleanse me as I try to blink myself sober. I make no eye contact with anyone and just nod to say that I am ready to do my job. Choristers, old and young, in frills of white and red, leave by the side door and snake gracefully through the night to the main doorway. I walk in front of them and, despite my predicament, I manage to set an even pace.

Like Stuart Murdoch, I give myself to sin. Nobody must know, and especially not Mum. I am pleased that I do not immediately stumble, finding the steady walk a small comfort. The slapping plod of shoes on gravel helps, a metronomic certainty that I dial myself into. My only wish, as I look up at painted silver angels in the rafters, is that this will all be over soon. We stand and pause in the entrance. I glimpse an orange glow from inside and feel that childish shiver of festive excitement. It is Christmas Eve and I want to savour its special feeling. As we move inside, I look over to the right where Mum usually sits, but the sudden turn of my head brings new problems. A nauseating feeling rises from my stomach as a whoosh of winter hats slides by in a blur. I am not through this. I see Mum’s ginger hair and familiar winter scarf as she stands neatly holding tonight’s service sheet. Her presence gives me an urgent focus: I really must not fuck this up. For her, I will make it down the aisle. I look ahead and wait for the vicar to indicate for me to start the final ten metres of the procession, up to the altar.

I glance to see the ceiling spin as I hear the choir begin ‘Once in Royal David’s City’. It is beautiful and my spine tingles, despite everything. Breathing deeply, in through my nose, out through my mouth, I walk forwards in a ruinous haze, a sludge of Sheridan’s, vanilla and chocolate, glooping through my guts.

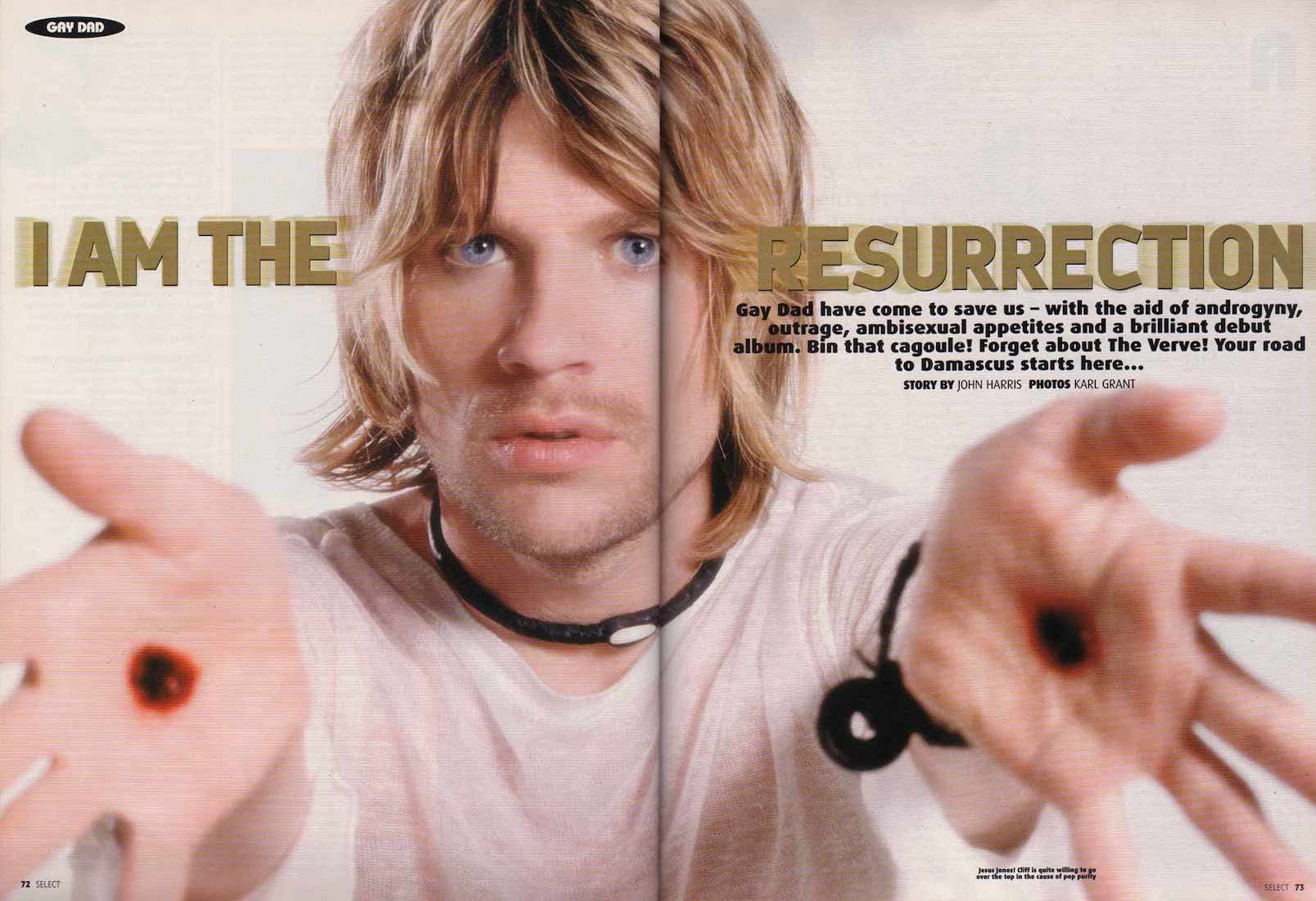

Gentle bleeps call from another universe, a wailing noise, a lost transistor radio bobbing in the waves of a strange electric-blue sea. Cliff Jones, Gay Dad’s singer, is presenting himself as an indie Christ and I’m eager to follow this self-declared rock star – and possible cult leader. I’ve seen him in crucifix pose on the front of the NME and with his stigmata oozing fresh red on the cover of Select magazine. He has nice hair and I feel ready to fall in love with a new pop star: all the better if he makes church more interesting.

‘To Earth with Love’ is the song that is sent to convert the fading Britpop masses. Part Bowie, part Slade, it is farcically grandiose but still very English, like a powdered wig down the chippy. Jones urges us to ‘use the latest sciences to make your world a better place’ as he invites us inside a ‘supernatural fairytale’. This is good, I tell myself, because really I prefer science to religion. It’s all done with a rock ’n’ roll heaviness that I want to like, but that I am still learning to want. Cliff, with his nice eyes, is speeding me towards a cosmic launchpad where Menswear and Mansun have just done their space training and their sparks are still flying from the thrusters. This time there are no cuff links, but the same unhinged show-off energy. Is this what the men’s loos are like in Soho House? A haze of hairspray and squeaking trousers? I turn a blind eye to the singer’s leathered legs, but they remain a concern as I grapple with the idea of life beyond the brown corduroys of Britpop.

Jones, gripped by the knowledge of his own imminent and assured superstardom, screeches the song’s title – ‘To Earth with love!’ – while summoning his own kind of glam-galactic spirit. It is hairy, this music, and I’m still not sure. Back at the launchpad, everyone’s forgotten to put on their flame-retardant suits. Gay Dad (does their name stand up to 21st-century scrutiny?) appear on the cover of all the main music magazines in quick succession. I am fascinated by the ‘saviours of rock’, a status bestowed upon them in a panicky flurry by journalists watching a Union Jack-wrapped carcass begin to turn grey. In my heart, I know Gay Dad are the last part of the pantomime, and probably the back end of the horse, but they still make me grin. I buy the CD single, only slightly furtively, from Woolworths on a Saturday morning. The cover shows a faux street sign, a pedestrian crossing icon on royal blue. I follow.

Music is a scaffold and by climbing across its joists, we build connections that lead to new beams, some of them right angular, and some of them exactly where we expect. Dad’s imposing record collection intimidates us, but we replicate his towering slabs of vinyl in miniature in our bedrooms. His Serge Gainsbourg CDs travel mysteriously to other parts of the house. His Shirelles record takes a holiday to the loft. My CDs and cassettes multiply, outgrowing both their shoebox and my newly added Cadbury’s Crème Egg tray. It feels Britpoppy to store my music in confectionery boxes, which I borrow from Maynews. Claire’s tapes reach up the wall in unsteady columns, tottering beside her black ghetto blaster, with Prince at their base, Tindersticks and David Devant in the upper levels.

Back in church, my granny’s harmonies are in my head. She takes the low notes, like a humble garden bird, and I want to do the same. Her gentle undertones make the high notes reach higher. On this cold, dizzy Christmas Eve, I think of her understated, supportive vocal and the thought steadies me. Somehow, and possibly through divine intervention, I lead the choir all the way up to the stalls without the crucifix clattering sideways into a pew. It sways but I correct myself, a woozy ship that finally – thank God! – finds harbour. My final task is to place it in a brass-lined hole at the front of the altar. I take it very, very slowly, watching its descent with grave concentration. I sigh inwardly as it clunks reassuringly into an ancient groove.

Anna Doble, December 2024

Sorry – I’m not reading that in your blog – I’m reading the actual book at the moment, so I’ll wait until I get to that part. Thanks for the constant entertainment, your intelligence, immense knowledge and yet, wit and sense of the playful and ridiculous.